Afrobeat, Chiaroscuro, and Video Games: On Immersion into History

November 1, 2023

Aisha Valiulla, T. H. Breen Digital Media Fellow, 2023--24

In October, Dr. Judith Byfield gave a talk in Harris 108 on ‘Serendipity and the Historian’s Craft,’ which was a pleasant reminiscence of the people, places, and coincidences that constituted her archive and shaped her research and career trajectory. The day after, she was generous enough to reflect for me in greater detail on various experiences, sobering and surreal, that informed her career. In recounting graduate-student exploits, conversations with peers, and plantation tours, she underscored the power of narrative, the importance of imagination, and the duty of historians to remember and reproduce the humanity of our work for students.

In 1988, young graduate student Judith Byfield was researching Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti (1900—1978), a Nigerian activist, suffragist, and educator who had led a famous tax revolt in the 1940s and was considered one of the leading faces of Nigerian independence and nationhood in the post-war years. As it so happened, Ransome-Kuti’s son was Fela Anikulapo-Kuti (1938—97), founder of Afrobeat, a music genre that combined West African highlife and Yoruba traditional music with American funk and jazz. He was also an outspoken political critic, philosopher, poet, pan-Africanist activist, and overall charismatic sensation. Her friends from the University of Ibadan insisted that she had to “experience Fela,” and so off they went to the Shrine, the dance club/community center that Fela Kuti had built in the 1970s. It was a “surreal” experience, she recalled. Fela performed shirtless, there was a haze of pot smoke in the air, and there were booths on the side of the stage in which female dancers accompanied the show on stage.

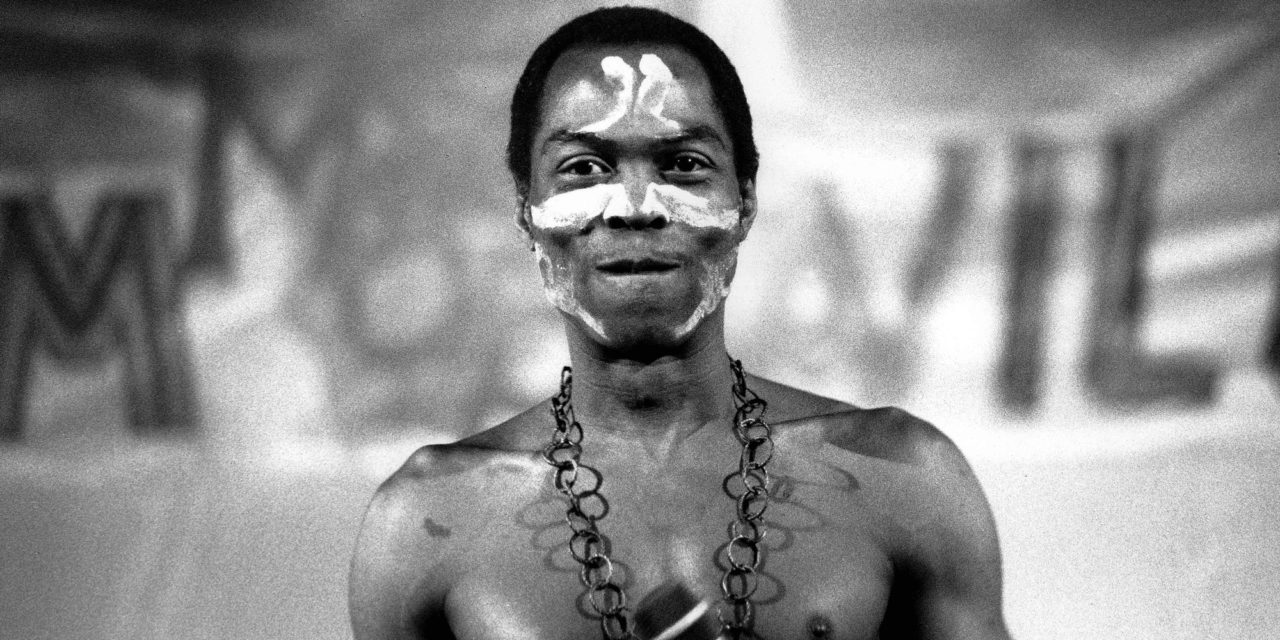

Below: Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, the King of Afrobeat

Fela Kuti’s songs are no three-to-five-minute beats, over and done with a hook and a chorus sandwiched in the middle. Most of his songs, deeply incisive and critical of politics, corruption, neo-imperialism, and authoritarianism (to name just a few topics), range from fifteen to thirty minutes long. The focus is as much on instrumental prowess—Fela’s band was famous for using two baritone saxophones at a time when most bands only used one—as it is on Fela’s incisive and evocative lyrics. The Shrine, later burned down and now resurrected as the New Afrika Shrine by Fela’s children, was a mythic music destination in its heyday. And while Fela Kuti’s political, musical, and philosophical influence on Nigerian and African culture is difficult to overstate, what interested me was that ‘experiencing’ Fela in all his surreal glory was part of Dr. Byfield’s historical research.

It is an obvious thing to state that a historian’s archive expands beyond the tangible and perhaps easily-decipherable remnants of past lives. Dr. Byfield reminded me of the necessity to seek out ‘experiences’ that connect us with our subjects, as rudimentary or even pedestrian as those experiences may seem. For instance, she mentioned touring various plantations in Jamaica as an assistant professor and recalled the vastly different choices that two had made in presenting the 19th century plantation life. One, Rose Hall Great House in Montego Bay, gave what she called the “HGTV tour of slavery,” extolling the legend of the ‘White Witch’ of Rose Hall, the beautiful mistress whose myriad husbands died mysteriously one after another, and sumptuous elements of her mansion: the silk wallpaper, the Queen Anne chairs, and great Italian villa façade. Today, the website touts Rose Hall as one of Montego Bay’s premium destinations for weddings. Were one to venture down into the basement, however, the less aesthetic parts of the hall’s history would become apparent. At the entrance to the cafeteria, Dr. Byfield remembered, was a table upon which they’d displayed a big bear trap that was used to catch runaway slaves. The wall behind the slave trap was covered with runaway slave advertisements.

Left: Rose Hall Great House, Montego Bay, Jamaica. Right: slave trap (courtesy Dr. Byfield)

By contrast, another plantation she’d visited in Jamaica presented an entirely different story. There had been an uprising and the great house had been burned. Only a fragment of the structure was left standing, and it had been left to remain as thus. Rather, the slave quarters had been reconstructed and they’d placed blacksmiths using period-appropriate implements to recreate the lives and contexts of those whose labor had paid for the wealth that allowed for Old World façades and silk-papered walls. The lesson in the power of presentation and perspective was a memorable one. “Till now,” she told me, “I still use those slides when I teach my Caribbean history class.” Her students see firsthand the difference in how the same period is presented. For most people, university history courses might be the only exposure they get to in-depth history. As historians, it is not only our responsibility, but our duty to present the past with all its life. “You want to leave a mark on them,” she observed. “Even if they don’t remember the details, they’ll remember the experience of what it was like.” From her own university days, she fondly remembered Art History professor Perkins Foss, who, during a class discussion of masquerades, literally danced the masquerade before them.

The takeaway is the willingness or creativity, as she puts it, to flesh out the story of a historical artifact, practice, or person through diverse methodologies and perspectives. When she changed her dissertation project to work on the tie-dye industry in Nigeria, her main advisor was Marcia Wright, a gender and labor historian of East Africa. Whereas her other professors asked herif she had enough material to justify such a project, Dr. Wright’s response was, “Well, you’re going to have to be creative.” As Dr. Byfield remembers, “That sealed it for me. Because I knew she had the flexibility in the way she thought; she wasn’t married to only one way of pursuing information.” Indeed, Wright’s multi-layered exploration of Bwanikwa’s life, a Zambian woman who’d undergone multiple enslavements and ended up at a Christian mission, where her brief autobiographical profile provided the foundation for Wright’s research, is a masterpiece in flexible historiography. It is the reconstruction of the political, economic, and cultural landscape in which a father was forced to pawn a beloved daughter, in which resistance and servitude undertook multiple forms, and in which self-ransoming could also be an act of identity assertion rather than capitulation to and acceptance of one’s own monetary value.

My interview with Dr. Byfield illuminated the fact that underlying our hypotheses that we hope the archives bear out and our speculations based on evidence a, b, and c is the imaginative exercise that we undertake as narrators of other peoples’ stories. To be able to immerse our audience in the past, our work needs to paint images as deftly as it defends arguments. Whether it be the sheer literary craftsmanship of Jonathan Spence’s academic monographs, or the vibrant inner lives that novelist Hilary Mantel breathes into Tudor schemers and dreamers in Wolf Hall, or the BBC adaptation of Wolf Hall that filmed only in daylight and candlelight (reminding us that chiaroscuro was a lived reality), narratives that bring subjects and their worlds to life are both appealing and accessible to a wider audience.

Below: a still from the BBC adaptation of Wolf Hall

Another avenue of wordless immersion? Video games. Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed franchise is one of the most popular and breathtaking examples of open-world single-player games set in specific historical periods. After its famous early trilogy set in Renaissance Italy, the franchise has expanded to include stories set in Ptolemaic Egypt, revolution-era France, Ming China, and most recently, 10th century ‘Abbasid Baghdad. Through beautiful graphic rendering and intricate attention to historical detail, players can literally "play [their] way through history" (as the franchise's catchphrase touts) by parkouring inside the Cathedral of Notre Dame, whaling with harpoons in the 18th century Caribbean, helping assassinate Julius Caesar, and crashing the second Continental Congress. My point with prestige television and open-world video games is that there is a public hunger for history, and specifically history told well. Through both her talk and this interview, Dr. Byfield reminds us that as historians, it behooves us to join in and bring the past to similarly vivid life.

Below: still from Assassin’s Creed: Unity: the playable character amidst the rafters of Notre Dame

All of Dr. Byfield’s quotes are from our interview, recorded Fri, Oct. 13, 2023.