Assumed Identities, Exhumed Bodies: Scandals in 14th Century Mamluk Lands

October 1, 2023

Aisha Valiulla, T. H. Breen Digital Media Fellow, 2023--24

This post is the result of an interview with our own Dr. Jonathan Brack, historian of medieval and early modern Iran and the Mongol Empire. In September, he was kind enough to share with me some of the most interesting and odd occurrences in the fascinating socio-political milieu of 14th century Mamluk Egypt. It is a story of false identities, grand claims, paranoid sultans, and crumbling bones. And if it whets your appetite for more, you’re in luck! Dr. Brack is teaching a new seminar in Winter 2024 titled “Tricksters and Charlatans” centered on mischief-makers in the medieval and early modern Mediterranean.

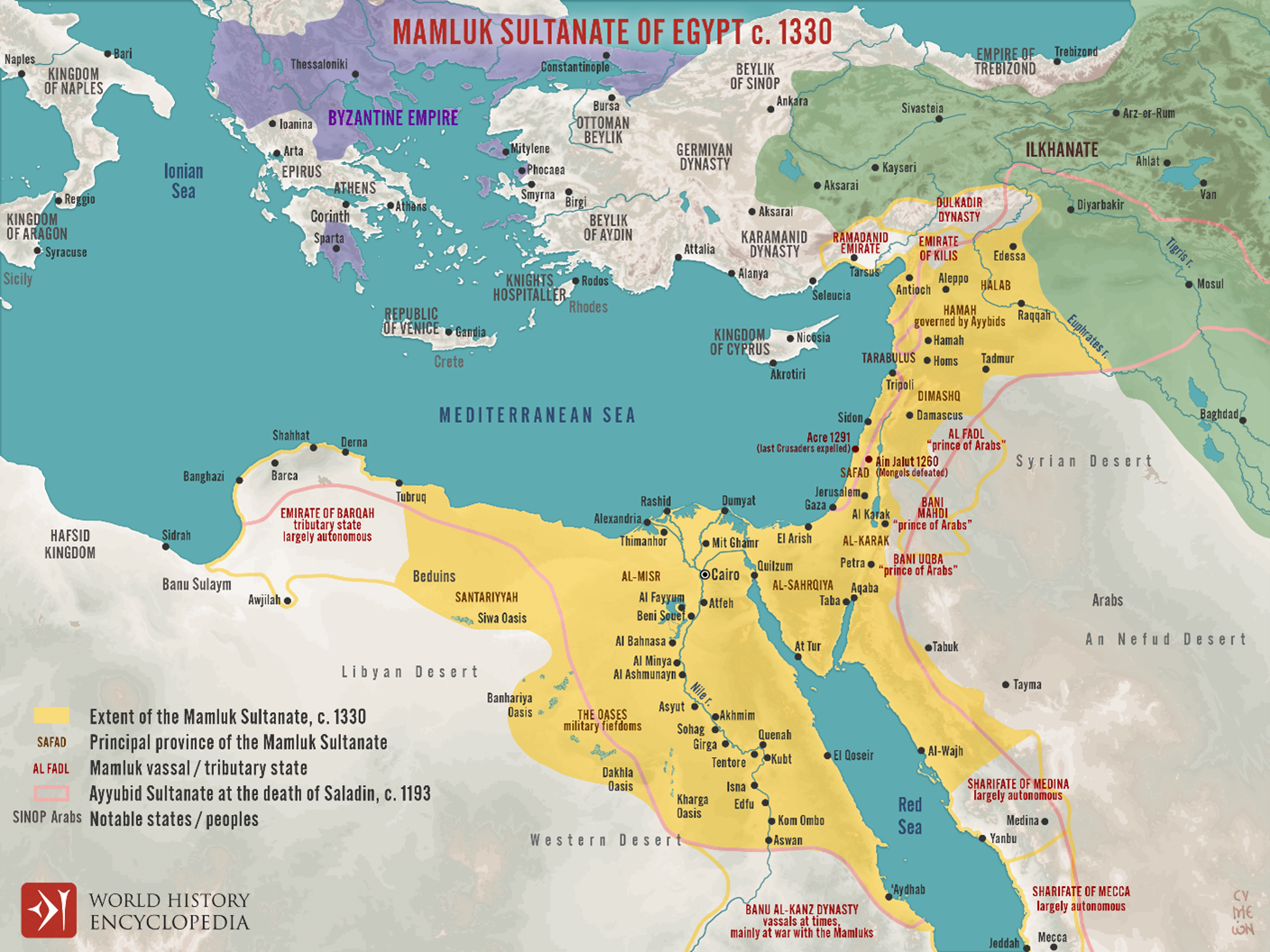

One Friday in the year 1352, in a small village in the countryside of Mamluk Egypt, a man with a ten-person entourage appeared and claimed to be the long-lost Sultan Abu Bakr al-Mansur, back to claim his throne and his crown. But how could this have been? Such a sultan had indeed existed ten years ago and ruled for a brief two months before he was deposed, imprisoned, and two short months later, executed. The mysterious man, later immortalized as Abu Bakr the Imposter, claimed he had been secretly freed before his execution by a sympathetic ally and had spent the past ten years hiding in Gaza, then an important Mamluk city and military waystation. However, the governor of the nearby town of Safad had his suspicions and sent word to the Sultan in Cairo, who demanded the imposter be sent to the capital city under heavy guard.

Some fifteen years back, a similar saga had played out, only this time the setting was not a dusty village in Mamluk provinces, but splashed across the Ilkhanid empire (c. 1256—1335). It began in 1322 with the rebellion of Temürtash, Mongol governor of the province of Anatolia, ostensibly against Abu Sa‘īd, ninth and last Ilkhanid ruler, but in reality against Temürtash’s own father Chupan, who was the de facto ruler of the empire and supreme military commander. Though Temürtash claimed to be the Mahdi, the foretold Messiah in Islamic eschatology, his father Chupan quickly squashed his son’s rebellion. Initially, the errant son faced few consequences; through Chupan’s intercession, Temürtash was even reinstated as governor of Anatolia. A few years later, though, the ruler Abu Sa‘īd turned against his overbearing general; fearing for his life in Ilkhanid lands amidst the crackdown, Temürtash fled to the Mamluk court in Cairo. The Mamluk Sultan at the time, Nāsir Muhammad ibn Qalawun (d. 1341), felt threatened by the charismatic and powerful Temürtash and summarily had him beheaded in 1328.

Nine years later in 1337, amidst the disintegration of the Ilkhanate empire, a man with a black veil over his face surfaced in Iran, claiming to be the Mahdi Temürtash, miraculously alive. That Temürtash’s son accompanied the veiled man only reinforced his claims. Back in Cairo, Sultan Ibn Qalawun was enraged; a long reign in the cutthroat world of Mamluk politics had made him paranoid, and spies whispered of this re-surfaced Temürtash raising an army against the Mamluks. Perhaps there was truth to the rumor—the Mongol princeling had certainly had admirers, and who was to say some of the Mamluk commanders, swayed by his charisma, hadn’t let Temürtash escape his own execution? What was an old and angry sultan to do?

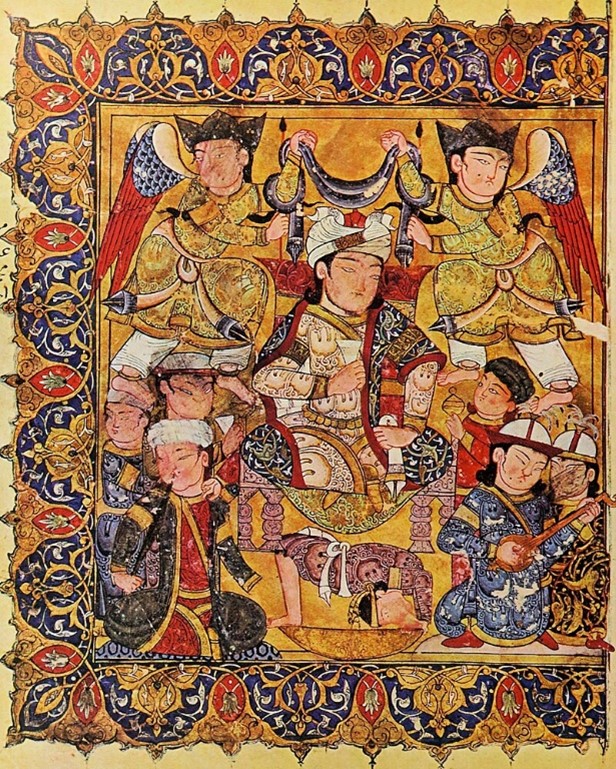

(Below: Mamluk court scene, possible depiction of Sultan Muhammad Nasir ibn Qalawun. Maqamat al-Hariri, c. 1334)

Exhume the body of the executed Temürtash, apparently! The Sultan had the grave reopened and the decade-old bones taken out. Gathering a group of diviners, he had the sword of Temürtash brought before them and asked them to use their metaphysical arts and determine whether the owner of the sword was dead or alive. Dead, to be sure, they all said. But the Sultan remained suspicious until the veiled claimant died and was revealed to have been one of the slaves of the definitely-dead Temürtash, whose “remarkable resemblance” to his former master made him a useful figurehead for Temürtash’s son Hasan to claim some Ilkhanid territory and perhaps establish a new dynasty.

Fifteen years later, though the motivations of Abu Bakr the Imposter were less clear, his reception in Cairo was as hostile as Temürtash’s had been. After some torture, it came to light that the man was actually Abu Bakr ibn al-Rammah, an official from the town of Safad who “had beaten and killed the police chief” of one of the nearby villages and sought to escape not into obscurity, but into a sort of political immunity (translation provided directly by Dr. Brack, Oct. 2023).

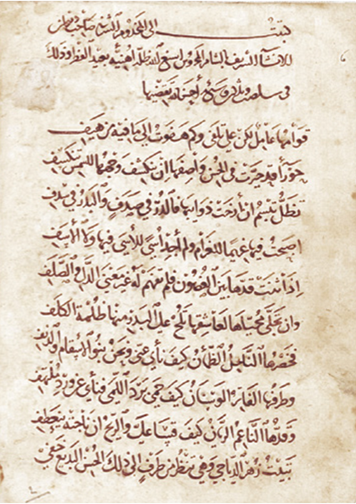

What do we make of these two incidences of assumed identities? Indeed, they are such odd occurrences ending in historical ‘dead ends,’ so to speak, so a better question might be, how do we know about them in the first place? These two anecdotes of ambitious imposters were grouped together in a 14th century biographical dictionary written by a renowned Mamluk scholar, Khalil ibn Aybak al-Safadi (d. 1363) who, as his surname or nisba indicates, hailed from the town of Safad. The medieval Arabic biographical dictionary genre was about showcasing the ‘crème de la crème’ of Muslim society, a ‘who’s who’ list of sorts, and were often spartan in their structure: birth and death dates, marriages, and number of children. That al-Safadi’s massive tomes—indeed, one of his biographical dictionaries spans thirty volumes!—included mysterious imposters and paranoid corpse exhumations indicates the evolution of the genre by the Mamluk period. Abu Bakr the Imposter certainly was not among the best the Muslim community could offer—but his story, along with that of the Temürtash doppelganger, certainly was alluring to an urban, public readership.

(Below: Folio from al-Safadi's al-Tadhkira, vol. 5, 6, or 7. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin)

Al-Safadi was writing at a time of mass ‘literarization’ of Arabic scholarship, where historical annals and biographical dictionaries expanded beyond traditional themes and included more anecdotes, more context, and more literary flourishes. Unlike the Persianate Ilkhanate cultural milieu where literary production relied heavily on court patronage, resulting in advice literature and political themes, the Mamluk literary world was less reliant on courts and therefore, much more expansive in its scope. The audience for Mamluk scholars was the larger public rather than an elite patron. As a result, biographic entries for instance became fleshed-out stories of lives lived and, for many of their readers, windows into different cultures and social classes. For instance, al-Safadi’s account of a Mongol princess on her way to make the Hajj, the required pilgrimage to the Islamic holy land of Mecca, also mentions her prowess as a hunter and horseback rider, along with her religious piety. But as the two accounts of Mamluk-era identity theft show us, grouped together by al-Safadi in his dictionary, not all notables were necessarily noble.

People claiming to be long-lost nobles and notables of various sorts is a universal occurrence. One only needs to point to the number of women claiming to be the Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanov, with Anna Anderson being the most (in)famous of them all, whose story inspired the 1956 movie Anastasia, which earned Ingrid Bergman her second Oscar for Best Actress. The number of ‘False Dmitrys’ who claimed to be the dead Tsarevich Dmitry, youngest son of Ivan the Terrible (d. 1584), is both hilarious and indicative of the universality of such claims. Indeed, as renowned historian Natalie Zemon Davis showed us with The Return of Martin Guerre, peasant identities were as susceptible to theft as noble ones. In such deceptions across time and place, we see the allure of power, wealth, and prestige incumbent upon the persuasive power of an individual’s wit and navigation of political, social, and material culture. We see a common, human thread of individuals creating opportunities for themselves and the machinery of social and political brokers who sought either to support or destroy them. We see human ingenuity and gullibility, paranoia and pragmatism—familiar sentiments all, transcending beyond specific historical contexts to endure long after these individuals, imposters and veiled messiahs alike, are gone.